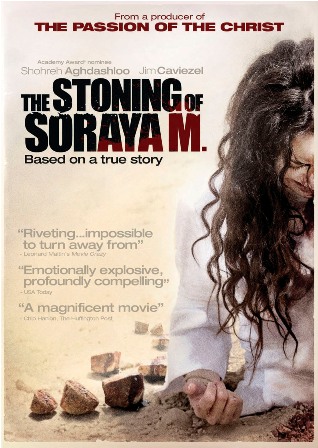

On a professor's recommendation, I sought out The Stoning of Soraya M. (2008), a dramatization of Freidoune Sahebjam's 1990 novel La Femme Lapidée, based on a true story.

This film presented me with a problem. As I have mentioned previously, I maintain a list of horror films I have seen. Keeping this list raises questions of what films qualify for genre classification. A previous post discusses my mode of definition. In that discussion, I decided that the central requirement of the horror film is that it horrifies the viewer.

When Soraya M. was finished, I faced a conflict of whether to include it as a horror film on my list. On the one hand, the film was certainly horrifying. It tells the true story of a woman vicitimized by a conspiracy to abuse Islamic law in 1986 Iran. Part of me felt that categorizing the film as horror cheapened the real-life tragedy behind it. This aroused a concern that I may be harboring a prejudice that horror is inherently cheap, which compromises the integrity of this blog.

It appears that the classification of this film will be the ground upon which I must again discover and defend my disposition towards this genre.

The Story

The Stoning of Soraya M. has a lot in common with The Stepford Wives (1975). Stepford centers on two women banded together to modernize their position in their male-dominated community. These women uncover a plot by the men in the community to murder their wives and replace them with animatronic slaves.

Soraya and her aunt are a similar pairing working towards a similar goal. The aunt uses her good standing with the men of the community to protect Soraya, finding her a job looking after the home of a widower. The aunt uncovers a similar murder/replacement plot, here with the men spreading a rumor of adultery, so that Soraya can be executed under Sharia law, leaving her husband free to marry a young girl.

It is somewhat uncomfortable to say that The Stoning of Soraya M. and The Stepford Wives have similar "plots." It seems offensive to the memory of the real Soraya and other victims of oppression. Still, in a vacuum, both films tell similar stories.

Why Now?

One standard question that pops up when reviewing films is "Why now?" When the source material is not contemporary, it helps to ask what is so relevant about the story to warrant attention today. What anxiety or sense of injustice does this film appeal to?

Just to deal with cynicism quickly, it should be noted that Sahebjam, the novel's author, died in March 2008. This film of his most famous work was produced in 2008 and released in March of 2009. Barring a great coincidence, the filmmakers could have used Sahebjam's temporary resurgence into the public consciousness as free publicity, with his passing as an impetus to produce this film quickly. Less cynically, one could view the film as a tribute to the life of the author, though I'm not convinced the industry often works that way.

Considering the actual stoning as a civil rights issue, the film is not necessarily a call to outrage over the death of this individual. When the film was realeased, Soraya Manutchehri had been dead for 23 years, and Sahebjam's novel had broken the story 19 years prior. Rather, the film seems to be part of the West's attack on Islamic culture.

It is not my place to weigh in on the civil rights of women under Islam, but the foremost criticism in recent years has been against the burqa, as a symbol of the oppression of women. But to me, it seems that outrage over the burqa is just another path to attack Islam itself.

The film concerns religious law, and how it can be abused to horrible effect. But the film doesn't just criticize the law and the men who twist it. It targets Islam as the culprit, and portrays the faithful in a very negative light, not unlike cultists of the horror canon (compare the mob's cries of "God is great!" to the "Hail Satan!" of Rosemary's Baby). In fact, by the end of the film, the women are almost secular characters. Soraya never invokes God in the scenes leading to her death. Instead, she appeals to her aunt to keep her memory alive, which is the closest thing to a secular afterlife. Soraya's apparent lack of faith seems purposeful. Having her invoke God before her execution would have been the classic opportunity to differentiate moderate Islam from fundamentalism, but instead, the film has nothing good to say about the faith at all.

Furthermore, I am made suspicious by the cover of the film, which proclaims "From the producers of The Passion of the Christ. I suspect that the audience targeted by this credential is an audience that is looking to have their fears of Islam reinforced.

Figures of Myth

To counter my worry that it is disrespectful to address a factual story like a fiction, I look to other films that should raise the same quandry. There are many dramatic films that rely upon factual misfortunes, but in those films, the characters are mythologized. It could be argued that the way a historical person is mythologized into a character is essential to human culture. They become the malleable elements of oral history. In the same way that George Washington was remade into a paragon of honesty, or how Ed Gein has been repurposed into many a glorified campfire story, Soraya Manutchehri has been transformed from a victim to a martyr, and, if my analysis is credible, perhaps into a weapon against her own faith.

I conclude then that the burden of classification in these films falls to the filmmaker, and where I may recognize an intent to horrify, I am justified.

A New Tripartite Definition of Horror

There are three senses of horrified. The most common form is the experience form, like riding a rollercoster, or a jump-scene in a scary movie that tricks you for a moment into believing that your are in actual danger. The second form is experience-emotional, which uses the experience of the film to draw you in, where that emotional investment brings you in touch with some greater anxiety (for example, the audience's committment to Alex is essential to the realization of the dystopic horror of A Clockwork Orange. The third sense of horrified, simple emotional horror, does not apply to the horror film. This is witnessing the horrific without the distance of the movie screen. News footage or a snuff film could never qualify for the genre.

The Stoning of Soraya M., because it is a dramatization, cannot be the authentic, third sense of horror. Regardless of how accurate it may be, it will always be a movie, an image crafted to evoke an effect. Because I was horrified, I recognize it as a horror film. When I sat down to compose this, I intended to explain why the film was not horror. But I've convinced myself otherwise, and have added it to the list at #289.

P.S.

1. The execution sequence is truly horrific, more on par with The Passion of the Christ than with the typical execution scene in other dramas, which always seem to keep their distance and minimize the graphic depictions of suffering. In contrast, Soraya M. horrifies by drawing out the sequence, embellishing the throwing of each stone, and even employing a first-person perspective. This film is about the horror of this scene, unlike the memorable and affecting hangings of Capote which are nonetheless incidental to the greater story.

2. The titling of this film follows a trend noted in John Kenneth Muir's Horror Films of the 1970s. Many '70s horror titles were formulated as "The (some happening) of (proper noun), with a distinct rhythm to the phrase. This began with the like of The Reincarnation of Peter Proud and The Possession of Joel Delaney, and can be found more recently in The Exorcism of Emily Rose, The Haunting of Molly Hartley, and The Possession of David O'Reilly.

Not that it was necessarily intentional, but The Stoning of Soraya M. follows the pattern.

No comments:

Post a Comment