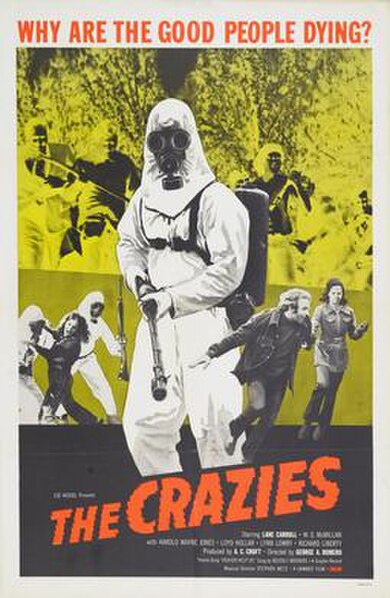

I was entertained by Breck Eisner's remake of George Romero's 1973 The Crazies, but I ultimately didn't care much for it.

Less consequentially, I think it suffers from being a good idea lacking in follow-through. I occasionally accuse sci-fi plots of starting with a good concept that gets dropped along the way. For example, I felt that Tony Scott's Déjà Vu had a pretty interesting time travel thesis going on, until it got dropped for explosions and an obligatory romance plot. The Crazies keeps Romero's concept of a virus that induces a murderous frenzy. In the original film, this creates rabidly violent victims, not unlike the experimental combat drug in Jacob's Ladder (1990). Eisner departs from this mold by allowing the infected to retain their composure, so that the virus compromises something else. Perhaps it creates paranoid delusions? For whatever reason, the film departs from its pseudo-zombie movie predecessor, giving us calculating killers instead of mindless hordes.

And that'd be fine, except that it is later shown that the infected are capable of setting traps and working as teams. Now, zombies don't kill one another, because they only hunt the living, and their compatriots are dead by definition. But why wouldn't the infected in this film attack one another? And go as far as to establish camaraderie?

Anyway, we're pretty well familiar with hippie horror as a liberal institution, if you elect to read Romero's original film as part of post-Vietnam disillusionment and a critique of government and military. So now it kind of makes sense that the new American radicals, conservatives and Tea Partiers, take up the same protest imagery to convey their impressions of "big government."

Liberal horror, when it addresses government and military, tends to criticize how America treats the outsider, calling upon injustices of foreign wars and general xenophobia. Romero's The Crazies comments on the American war practices against the Vietnamese, as well as the treatment of American soldiers as expendable. That film shows the tables turned, as the military is deployed against its own citizens, and even features a self-immolation, referencing the powerful imagery of Vietnam-era protest.

Liberal antiwar protest always seems to target an individual character, calling out the president on "war crimes" or what have you, and staking a hope for reform on the ousting of this specific character. The 1973 film gives faces to the politicians and military leaders responsible for the catastrophe, which demonstrates a belief in personal responsibility and accountability. This isn't particularly noteworthy until we consider the remake.

The 2010 version of The Crazies portrays the government in the absolutely most negative possible light. As an entity, the leadership remains entirely faceless, but we are able to see through its eyes by way of "big brother" spy satellites, which zoom in to the action on the ground periodically. This imagery is very similar to the telescope view used by the mutants in the remake of The Hills Have Eyes, which shows the stranded family as always being watched by their stalkers and murderers.

This is where I see a libertarian bent to this film: The government is portrayed as a malevolent entity, not as something human, accountable, and reparable. You can't vote those spying eyes out of office.

Counter to the faceless government and its faceless gasmasked drones are the regular, ordinary folks, led by the small-town sheriff, who would be capable of seeing after themselves if it wasn't for big brother's interference.

The selection of school and hospital as key battlegrounds comments on the political struggle for the control of these institutions. In the remake, the school is repurposed as detention center/hospital. The public school system has always been a contentious topic, but the hospital is relatively new, perhaps serving as a commentary on "Obamacare." We see that in this hospital, everyone is treated the same. The infected are strapped down alongside the healthy, because the authorities aren't interested in sorting through the patients. It is later revealed that those who were quarantined and the others who were shipped out met the same fate either way. Sound like "death panels" to anyone?

Finally, I think the "crazies" themselves have a political role to play. The characters are not portrayed particularly sympathetically. I think it would be fair to interpret the crazies as the political opposition to the central "conservative" characters. After all, it is technically the fault of the infected that the big bad government invaded the town to deal with the situation created by rampant psychosis, which of course, was created by the government when it leaked a toxin into the water supply. Compare this to an image of American social programs where the government has to clean up, for example, the homelessness problem, at the expense of the taxpayers, to solve a problem that the government helped to create in the first place.

At one point in the film, the infected become the arm of government agenda. In scene where the restrained patients in the hospital are systematically skewered by a crazy with a pitchfork, let's remember that it's essentially the fault of the government, first for not posting any security in this wing of the building, and secondly, because this maniac is achieving the same goal the military personel were going to carry out anyway. As in, when socialized medicine takes away your doctor and forces you to see someone else, the pitchfork man is the new doctor you can't trust, who kills you in your bed along with everyone else because you can no longer get the treatment you need.

Did anyone else get this vibe?