I promise this post discusses horror films. Please be patient with the exposition.

I promise this post discusses horror films. Please be patient with the exposition.Dualism

Think about your body. There. We've already proven the point I'm intending to make. You thought "my body." My body.

Let's draw out what makes this phrase suspect. If you are a religious person, you may believe in the soul, a god-given ego. If you are "of a secular mind," you may believe in the mind, another suspicious term. The idea of a dualism between mind and body is old and well-trodden. Philosophers of mind who wish to do away with the notion of the mind attempt to reduce it to functions of the brain. Others endorse the mind and rebuff reductionistic treatments of its mystery.

Regardless of what you believe about the mind or the soul (henceforth called the ego), our culture has 99.9% given in to dualism.

We are divorced from our bodies, and it is evident in our language and behavior. Myriad examples reveal this. We think of our bodies as the chariots of our egos. What is sickness? It is an affliction of our vessel. The naming of disease helps this process by creating distance from which we can address our afflictions. Sometimes the body grows in a self-destructive way. We have a phrase for this: getting cancer. We draw a sharp distinction between ourselves and the part of ourselves that we recognize as a threat. We can easily excise bits of ourselves when they don't suit the project of continually housing the ego in the body.

Perspectives on pregnancy fit this framework. Pro-choice interprets a pregnancy as an outside influence on the mother's body. Abortion is a cure for being afflicted with pregnancy. Pro-life is no different, where the fetus is a visitor to the mother's body to be safeguarded. The fetus is a stranger, something not an extension of, but different from, the body of the mother. Neither perspective is truly a bodily perspective; both are plays at forcing the body to submit to the ego.

Skin versus Flesh

I cannot speak to your experience, but "skin" is a very different word to me than "flesh." Skin has so many uses and meanings, while flesh is a charged word that evokes a sense of revulsion in me.

The colloquial phrase "pleasures of the flesh" speaks to bodily experience and all methods of living through the body, often by way of consuming other bodies. Eating, whether it be plant or animal flesh, is the assimilation of flesh from one body to another, lived entirely in the first person, not with the third-person detachment of the ego. Nonliterally (but still quite literally), sexual intercourse is much the same, as another consumption of flesh, a bodily pleasure derived from assimilation.

But there is another aspect of sexuality, the inability to live it bodily. This is the sexual fetish, which reduces flesh to skin. Skin is a surface, a mental object. Some skin is flesh, to be sure, but other skin no more material than the clothing or makeup it bears. Flesh is the object of bodily experience, but skin is the object of mental desire.

Fetishizing the skin is an intrusion into the bodily experience of the flesh. The sexual fetish makes the partner the object of mental desire, an object cast in skin. The ego then sets about to manipulate the partner's body like a tool, contorting, restricting, and adorning it to satisfy aesthetic requirements, binding or covering the body to modify its shape, or enlarging (perceptually) the foot or the breast.

Bodies are already skin before our egos, though. Modifying our skin, we can change anything outward about ourselves. But flesh refers to something inward.

Filmed Bodies

How does film treat our bodies? Usually, film treats the body as a skin. As a visual medium, it may be impossible to treat the flesh. Any filmed scene is essentially a fetishized experience of the body. There is nothing fleshly about pornography. Filming pornography is another mode of recrafting the body to make it satisfying to the ego. The fleshly encounter of authentic violence, of actual moving through another's flesh, is reduced to an aesthetic skin in film; the idea of the body is recrafted by the knife or the bullet. Hordes of skin-bodies are remade as aesthetic objects in any action flick, cut down in waves to satisfy the demand of the viewer that they visually transition from "alive" to "dead," whatever those terms mean. There is something pornographic to this.

Body Horror

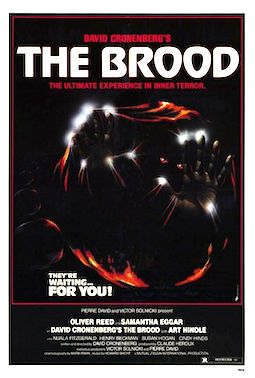

What does "body horror" do in this framework? Body horror is understood as fiction dealing with deformed and deforming bodies. David Cronenberg is the director most closely identified with this subgenre.

Following my exposition above, I require that authentic "body horror" portray the deformation of the body in question sympathetically. That is to say, I include, for example, Cronenberg's The Fly but not Carpenter's The Thing, because the Thing's malformed flesh is always inhuman, only resembling the human figure.

I suggest that body horror offers a special interaction with the dualism of ego and body, specifically that it at once recovers a sense of the flesh while simultaneously obscuring it.

Cronenberg's 1979 film The Brood is an example of the recovery of flesh in body horror. In the film, a woman's negative emotions manifest as asexually produced mutant children who channel her rage into violent acts. The film rejects dualism by showing a direct relationship between emotion and body, so that her rage is not lived mentally, but bodily. Furthermore, these children are not "children" in a conventional sense, understood as sovereign entities. Rather, they are the flesh of the mother (with no father to muddle the equation), extensions of her flesh, and she lives through them in part, just as much as she lives through her hands.

For the audience to experience a recovery of the flesh, the film has to circumvent the expectations of the audience. In a conventional horror film murder, the surface of the body conforms to the trauma like a tool purposed to receive the blow. Body horror goes further, peeling back the skin to expose the flesh. What lies beneath the skin represents chaos. We cannot predict what we cannot see, so in a sense, the flesh is illogical. That is what is unsettling. It is the simultaneous allure and revulsion of the flesh. The complexity of taste is, in all honesty, a mystery. At best, taste is familiar, but always unique. Looking at the flesh beneath the skin of a film character is uncomfortable, because for all we recognize, respond to, and perhaps even desire of the skin, the chaos of the flesh is hidden. Until it isn't.

Experiencing revulsion in watching flesh exposed in a Cronenberg film is a recovery of the understanding of flesh. The revulsion is not bound to the ego. It is an empathetic bodily reaction to another's bodily experience. You don't think your reaction to such a scene. You feel it.

But through body horror the audience also loses the sense of the flesh in the moment following the initial revulsion. Almost immediately, the exposed flesh becomes the new skin. We're back in the world of surfaces, where the malformed body is an affliction on the vessel of the ego. When the audience has the opportunity to react to the transformation as a new state of the body, it is reduced to just that, a state that the body is in, as temporary as any skin.

Pasolini's 1975 film Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom, a transplanting of de Sade's writings into fascist Italy, expresses the vantage of the ego, embodied by the fascist tormentors, who experience their captives as malleable fetish objects. The film also portrays the vantage of the body through the victims. As the victims are systematically reduced to objects by their tormentors, their suffering is increasingly lived bodily as resignation to the minimal level of survival sets in. Pasolini lets the audience experience both. When you sympathize with the victims, you feel that experience, and if you give this ugly film enough respect to actually think about why the antagonists commit these acts, you feel that experience too.

To paraphrase Martin Heidegger, the hammer appears as a tool for the possibility of hammering, and only when it is broken does it reveal itself as a real object of metal and wood. Showing the human body in chaotic disrepair recovers a sense of what we really are and how we live through these selves. But at the same time, we react by problematizing our bodies as objects to be repaired or otherwise overcome.

Intersection

What of the real-life relationship between flesh and skin? Flesh-desire intersects with skin-desire to shape the fit between the ego and body. To satisfy these intersecting desires, the ego crafts the solution. The bodily desire to create is met when the ego sets towards art, or perhaps child-rearing. The bodily desire of lust is met when the ego and body conspire to come as close as possible to the object of attraction, stopping just short of becoming it, knowing it fully. Two examples from horror come to mind, where the ego composes a practical solution to the bodily desire for transformation: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre's Leatherface and The Silence of the Lambs' Buffalo Bill don guises crafted from human skin, a material that is simultaneously flesh and skin.

What then of dualism? I now feel that ego and body define two realms of behavior/experience, somewhat distinct, but entirely inseparable.

No comments:

Post a Comment